29 Apr, 2019

Tourists out, turtles in at Conservation Centre run by Thai Navy

Phuket/Phang-nga, South Thailand – South Thailand’s famous beaches are visited by millions of tourists annually. But just a few kilometres off the coast of Phuket is an island where tourists are out, turtles are in. In an era when overtourism and beach closures are making headlines, Huyong island is a fine example of the need to permanently ban tourism and all forms of development in pristine, natural habitats in order to preserve them.

The tourist ban is imposed by the Royal Thai Navy, which runs the Turtle Conservation Centre, under the patronage of Queen Sirikit. The Navy is far better at enforcing controls than the local civilian authorities. In a candid presentation to Thailand-based foreign diplomats from 44 countries, it clearly showed how tourism growth, and the less-savoury “growth” in beach-front hotels and lodges, boats, water-scooters, beach umbrellas, etc., has destroyed the natural turtle habitats. Laws and regulations to protect nature have proved futile.

The diplomats were visiting Thailand’s second most important tourism gateway on a study trip organised by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) under its soft-power promotion policy to showcase the ongoing transition towards the sustainability agenda of the late King Bhumibhol’s Sufficiency Economy Philosophy (SEP). Although the MFA has taken diplomats on several previous annual trips to the late King’s Royal Projects in North and Northeastern Thailand, this was the first to South Thailand. The choice of the strategically located South Thailand region, close to the land border with Malaysia and maritime border with Indonesia, assumed added importance as Thailand is the 2019 chairman of ASEAN, under the theme of Advancing Partnership for Sustainability.

At each stop, the diplomats were exposed to the rich multi-cultural history and vibrant ecosystem of the Thai Andaman Coast and its recovery from the December 2004 Tsunami. Unlike a regular tourism trip, the idea was not to “promote” the destinations but rather to show how the higher and holistic national policy objectives are contributing to the inclusive, sustainable transformation of the island in line with its new status as Thailand’s Smart City.

Tourism is now the economic lifeline of the region. In 2018, preliminary figures compiled by the Ministry of Tourism and Sports indicated visitor arrivals of 14.38 million Thais and foreigners, up 2.64% over 2017. They generated estimated earnings of 477.3 billion baht, up 12.84% over 2017. In 2018, Phuket had a room count of 97,864 across 1,943 accommodation units. Low-cost carrier aircraft movements totalled 55,799 in fiscal 2018 (ending September 2018) up a whopping 19.73% over fiscal 2017, while non-LCC aircraft movements totalled 116,487 in the same period, up 11.10%.

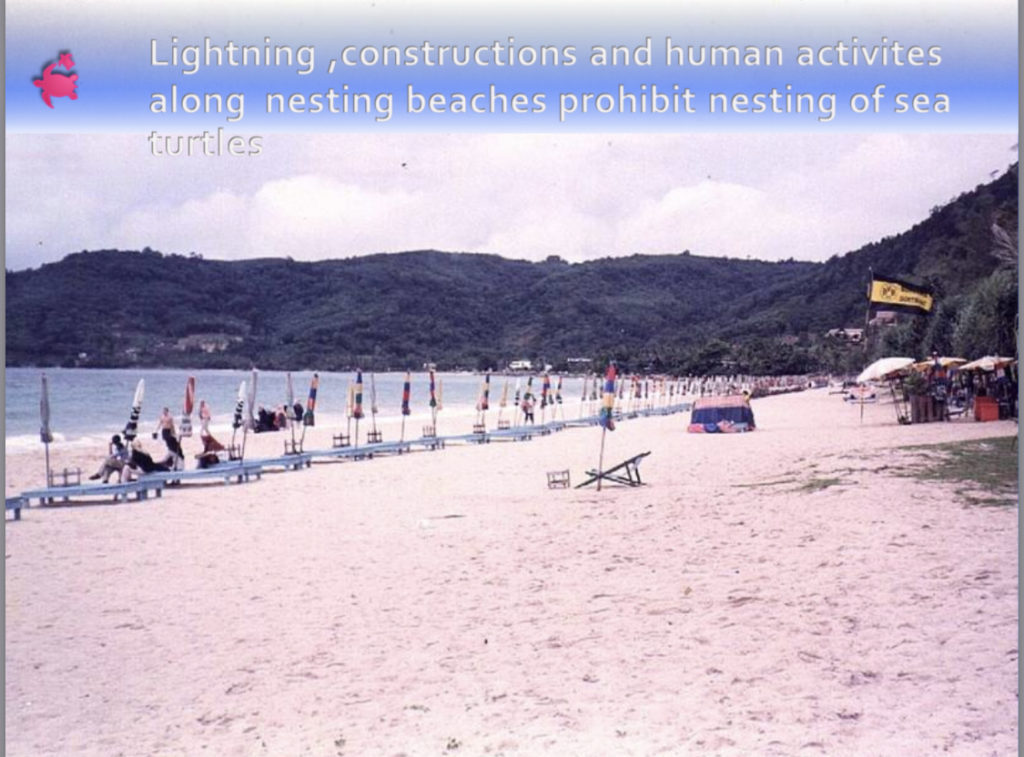

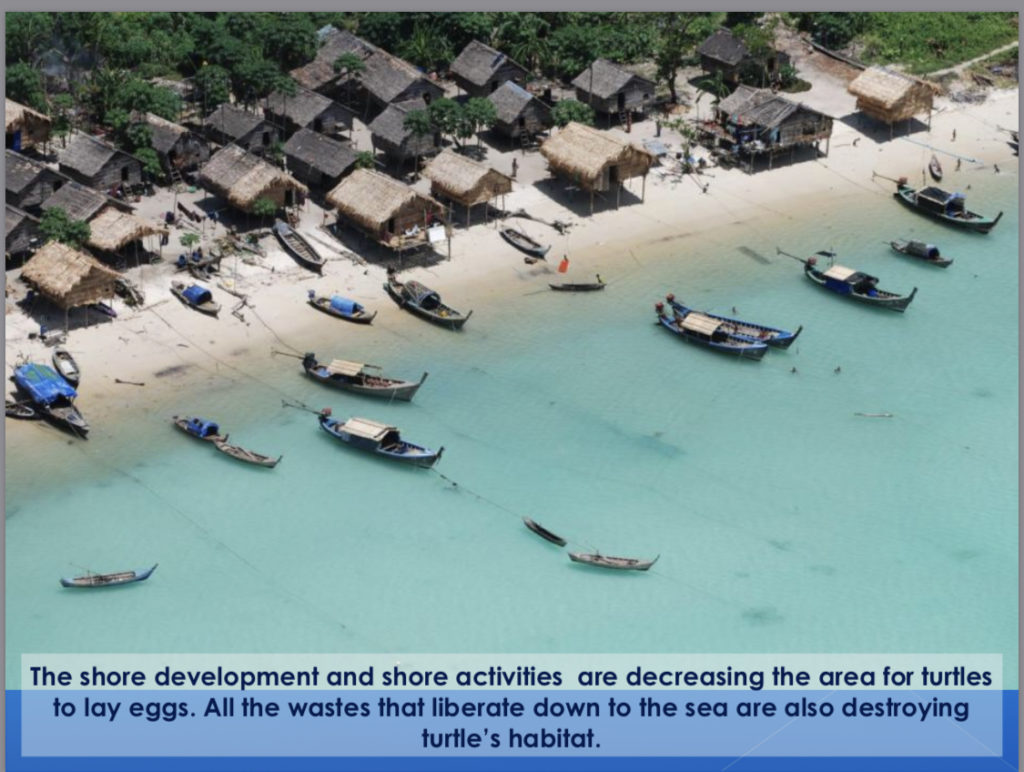

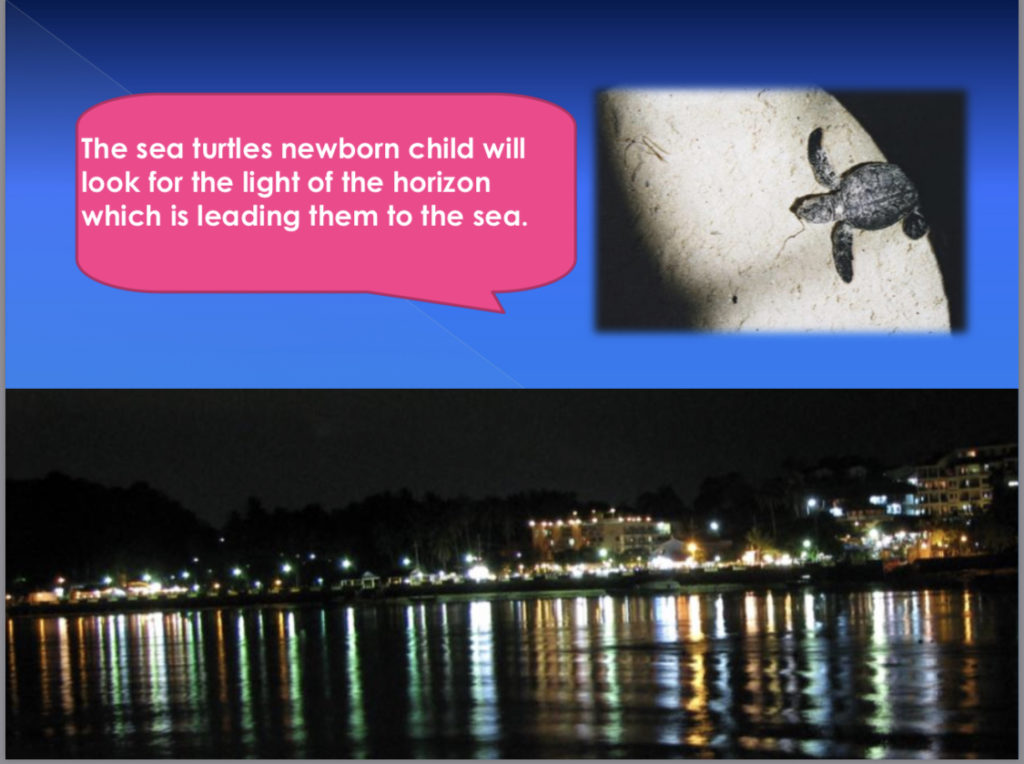

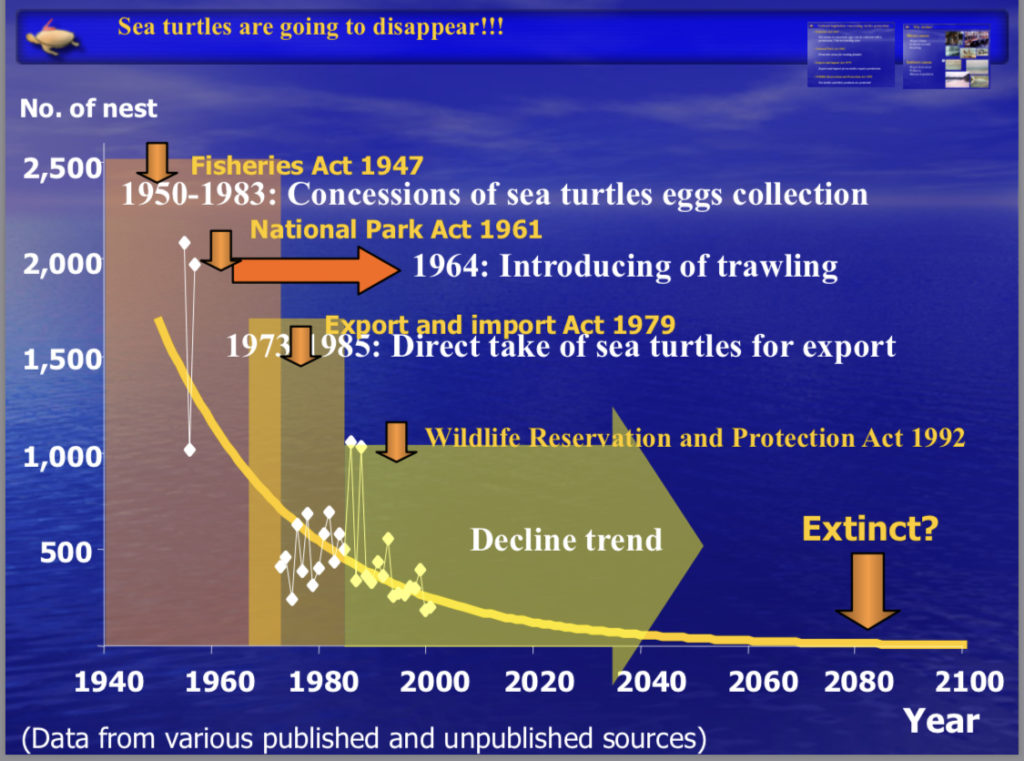

While these numbers may be economically eye-popping, the Turtle Conservation Centre highlighted arguably the core problem facing both Thai and global travel & tourism – how the obsession with economic growth is destroying the local ecology, aggravated by ripple-effect problems such as illegal fishing, over-fishing, poaching and pollution. In his briefing, Commander Surasak Inprom, Head of Special Public Affairs Division, Phang-nga Naval Base, flashed up the following self-explanatory slides:

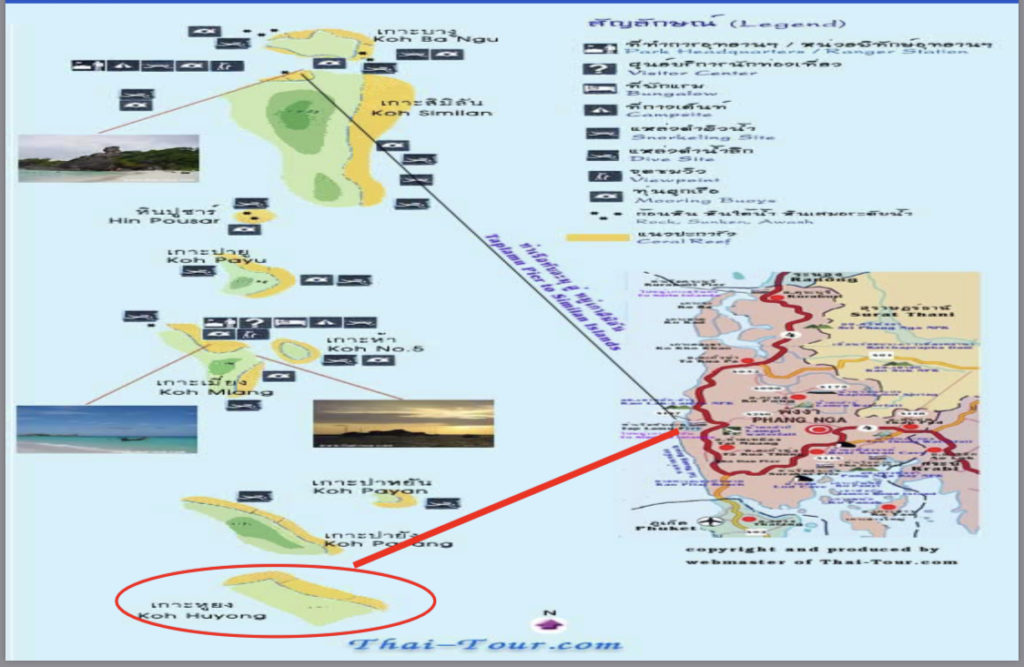

The diplomats were told how the declining turtle population came to the attention of Thailand’s Queen Sirikit. In 1995, on the Queen’s instructions, the Navy took on a new role that redefined “protection” of Thailand’s maritime borders to “protection” of the natural habitat from the tourism invasion. The Turtle Conservation Centre is located within the Phang-nga Naval Base. It collects hatched turtle eggs from Huyong Island of the Similan Islands chain and relocates them to the hatchery facility at the Centre. Each year, an estimated 10,000 turtles are provided with a safe environment to grow to an adequate size prior to their release back to the sea.

The path to turtle conservation. Huyong Island is at bottom left.

The three-kilometre Song Ngam beachfront (pix below) of the Turtle Conservation Centre is also development-free. Tourists are allowed to visit the centre, and can swim at the beach. But there are no beach umbrellas, vendors, massage services, water scooters and no resorts. Dormitory-style accommodation of 10 beds is available for 350 baht a night, used mainly by local Thais. But demand is high, with a long waiting period.

If short-term tourism development has wreaked havoc on the turtle population, long–term issues caused by global warming also at stake. Commander Surasak said that if the sea water temperature rises to 31 degrees Celsius, higher than the required balance of 29C, only female turtles will be born. One slide showed clearly that if the pace of tourism growth and development continues unchecked at its current pace, the turtles will go extinct by 2080.

The diplomats also participated in releasing turtles into the sea.

Commander Surasak briefing the diplomats.

The Navy runs another Turtle Conservation Centre at a base in Sattahip near the border with Cambodia on Gulf of Thailand. The budget comes from the regular Navy allocation and public donations. A UK-based conservation group organises fund raising projects with local young people. Donation boxes can also be found at some of the popular tourist attractions. I asked them commander whether the local tourism businesses contribute. He indicated not.

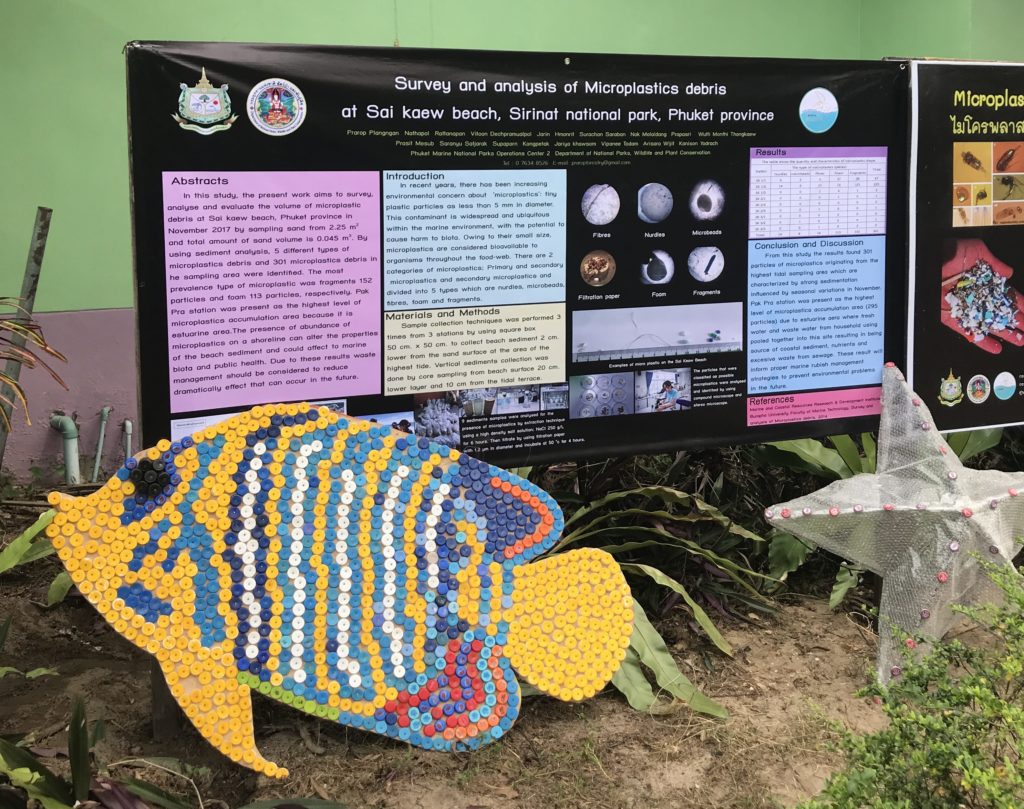

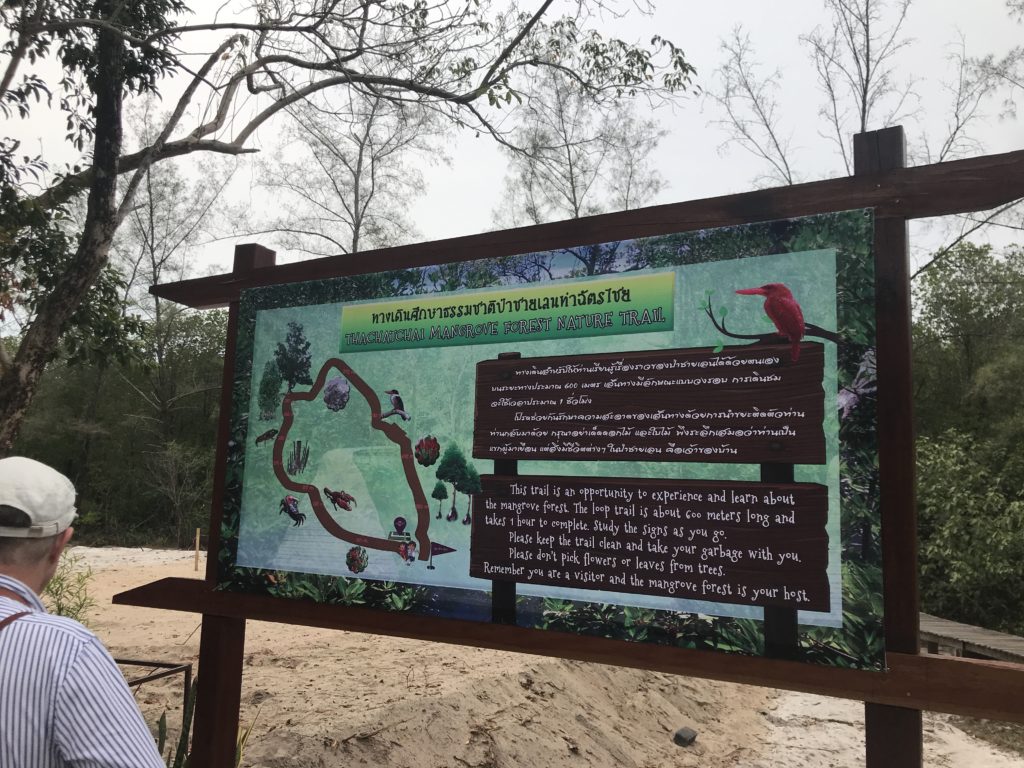

The diplomats were briefed on another environmental challenge at the next stop, the Baan Tha Chat Chai Phuket Marine Park Research Centre which oversees a mangrove forest on the northwestern coast of Phuket, close to mainland Thailand. The saltwater swamp is a nursery for plants and young marine life. Here, too, strict limits are placed on the number of visitors allowed on the one-kilometre boardwalk which runs through the mangrove forest. In a briefing, Centre officials also outlined the impact of marine pollution, especially microplastics, illustrated in the pix below.

More examples of the environmental damage done by tourism at the Baan Tha Chat Chai Phuket Marine Park Research Centre.

The map showing the roughly one kilometre boardwalk trail through the mangrove forest at Baan Tha Chat Chai Phuket Marine Park Research Centre.

If the natural environment is under siege, the cultural environment is somewhat better off.

Millions are gainfully employed, making Phuket and Phang-nga important examples of ASEAN socio-cultural integration. Due to its historic strategic location on the India-China trading route, Phuket has long been an ethnic melting pot. Old-town Phuket has been shaped by Hokkien Chinese immigrants, “Peranakan”, who migrated to many locations in the peninsula as tin miners and traders during the 19th century. In many parts of the island, Muslims of Malay descent make up the majority population.

The history of Phuket through four distinct eras (the jungle, the mines, the city, and tourism) is enshrined in Museum Phuket, a collaboration between Museum Siam and Phuket City Municipality. The exhibits take visitors through Sino-Portuguese colonial architecture found in the old town, and through presentations of clothing and food items unique to the Peranakans. Immediately after the Museum, the diplomats briefly visited an ethnic Chinese shophouse now converted into an elegant boutique hotel (pix below), a great example of how Chinese entrepreneurship excels at reinventing itself in line with evolving opportunities.

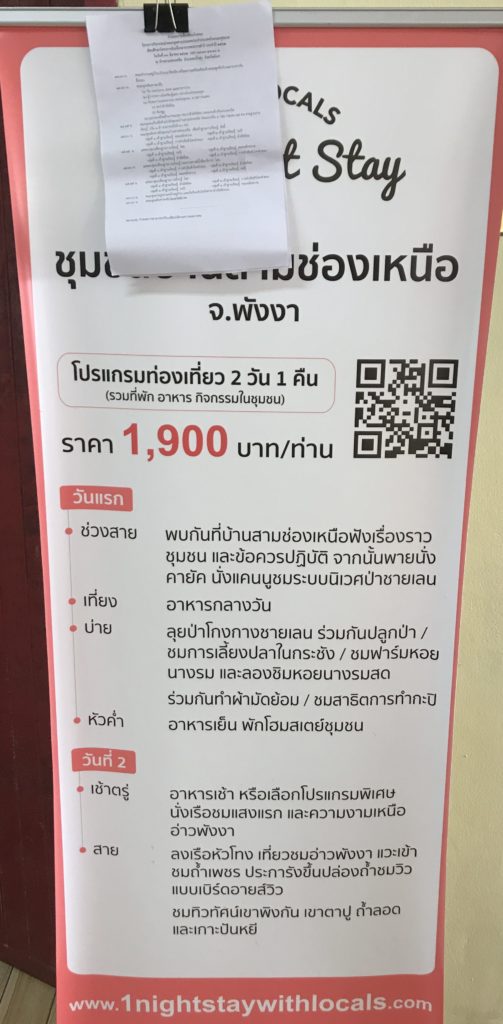

From Phuket’s Chinese influence, diplomats were taken to see the Islamic influence at the Baan Sarm Chong Nuea Community on the eastern coast of Phang-nga Province. The village sits on the confluence of three waterways, and is only reachable by a 3-minute boat ride. Most villagers are Muslim and have relied on fishing all their lives. In line with Islamic practise, alcohol is banned and all food is ‘halal.’ The villagers have recently turned to eco-tourism, with tours of the village and home-stays which have helped boost their income and raised awareness amongst visitors of the potential for sustainable co-existence of people and the ecosystem.

Tourists can go kayaking through the surrounding mangroves, guided by local youth trained to provide interpretation in English and increasingly in Chinese. The village has developed local methods of preserving daily catches, turning raw materials into ready-to-eat and saleable products, ranging from shrimp-paste to tea and soap. Other products include toys made from native Nipa palms, fabric bundles organically coloured, and shellfish fanning. All are sold under the “One Tambon One Product” (OTOP) scheme, a nationwide project to help commercialise indigenous products specific to grassroots communities. The diplomats were warmly welcomed with a dance performance and live demonstrations of how the products are made.

The Baan Sarm Chong Nuea village is on the left, as seen from the mainland.

Travel Impact Newswire Executive Editor Imtiaz Muqbil

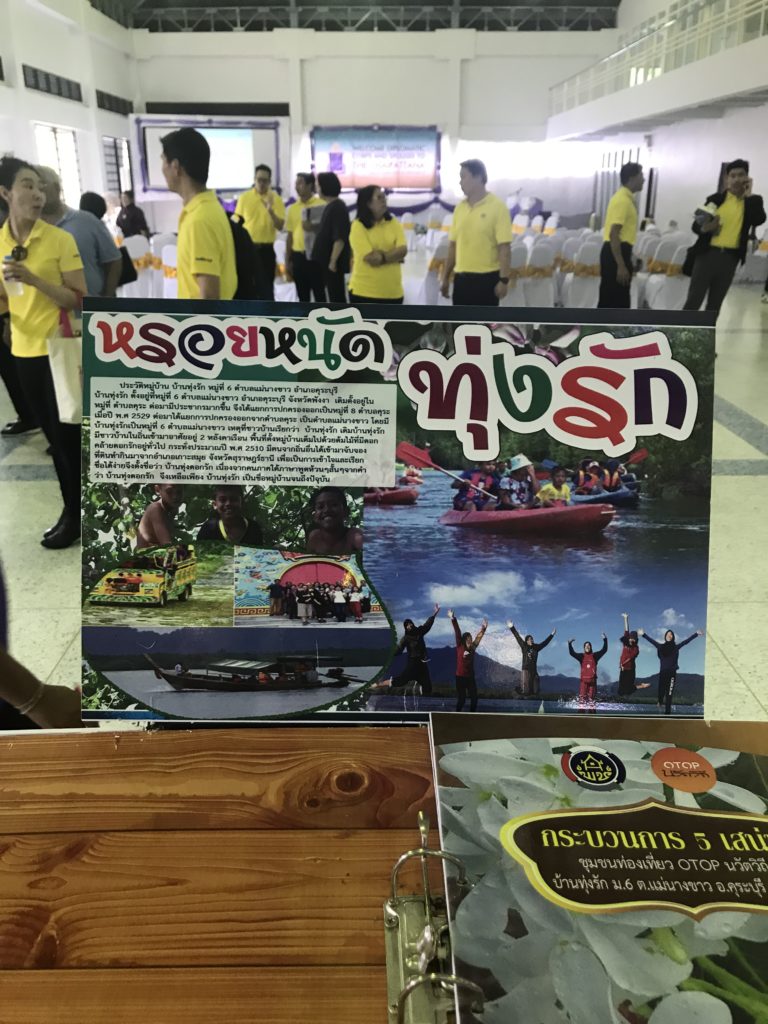

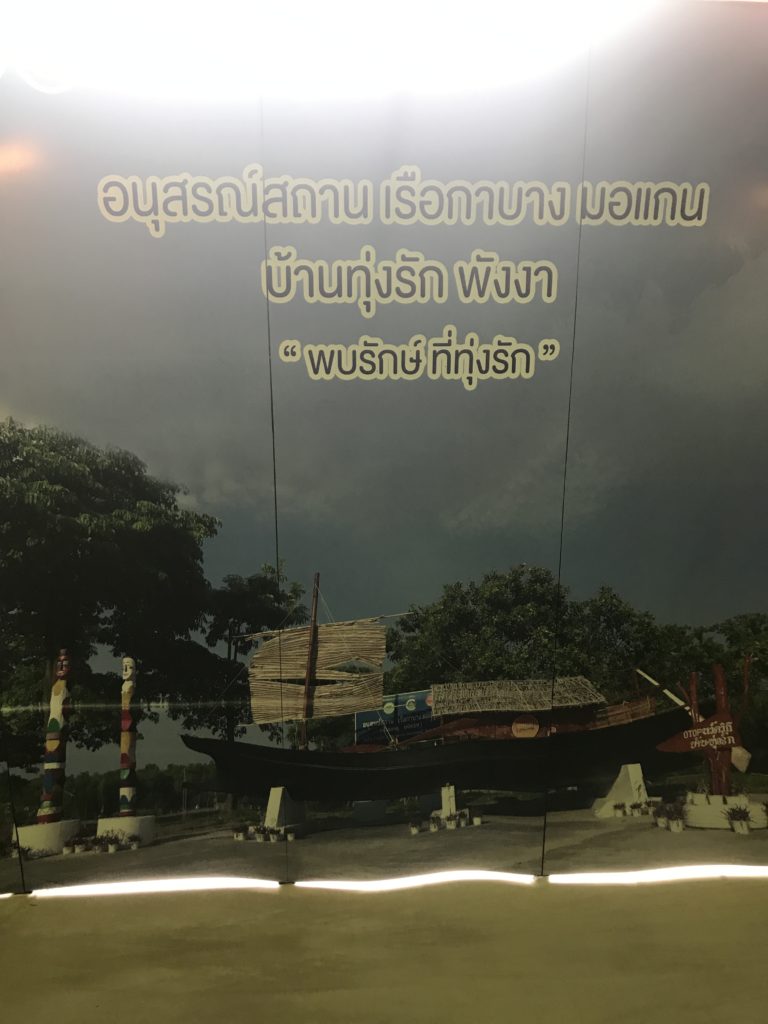

The next stop was the Province of Tung Rak (love meadow), named after a meadow in Kuraburi District of Phang-nga Province populated with blooming white gardenia. The area was home to a cashew plantation which was wiped out by the 2004 Tsunami. Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn commissioned the Chaipattana Foundation, in collaboration with the Thai Red Cross Society, to build a new community for the victims in that area and surrounding regions, using as a base the Sufficiency Economy Philosophy (SEP) of her father, the late King Bhumibol. Today, the 170 housing units built with full infrastructure facilities, including a hospital and a school, are considered to be one of the most successful village models for disaster management and recovery in the country. It lives up to the principle of “Building Back Better” and “leaving no one behind”.

As damaged fishing boats prevented the new residents from returning to their former fishing livelihood, the Chaipattana Foundation worked with governmental, private and academic partners to replace them with locally-made boats using fiberglass materials. Retired fiberglass boats are used in the construction of roads and artificial corals. The community also makes a range of OTOP products, many of which are derived from the artisanal fishing activities of the villagers.

The last stop was the Phuket Grand Marina (pix below), one of the iconic hot-spots designed to attract the rich and famous and promote Thailand as an ASEAN maritime hub. Located on the northwestern part of Phuket, the marina stands in the midst of luxury accommodation units. With zero tide restrictions, it also hosts an annual Yacht Show which attracts hundreds of high net worth individuals – a key customer segment being actively pursued by the Tourism Authority of Thailand.

Overall the study trip was a powerful reminder of the economic, social, cultural and ecological crossroads at which Thailand stands. By highlighting both assets and liabilities, the trip proved to be a powerful learning experience for both guests and hosts. Many of the ambassadors, especially from developing countries such as Mongolia and Sudan, said they gleaned a lot of ideas that could be of use in developing their own tourism industries. In turn, the Thai hosts got an opportunity to practise their presentation and communication skills in English. A win-win study trip, all around.

Liked this article? Share it!