4 Aug, 2017

How Thai tourism’s history deficit saw it lose a huge ASEAN@50 opportunity

Bangkok – As ASEAN prepares to mark the 50th anniversary of its formation on 08 Aug 2017, the Thai tourism industry has lost a major opportunity to celebrate the central role played by the Kingdom in ASEAN’s formation, and better understand the significant linkage between peace, ASEAN integration, diplomacy and travel.

Had there been greater awareness of this history, this month would have been a perfect time to organise nationwide events to help Thai travel & tourism recognize how ASEAN’s principles — the preservation of individual independence, territorial integrity and peace – laid the foundation on which the entire regional tourism structure stands today.

Very few in the Thai tourism industry would know that the establishment of ASEAN was a Thai initiative, drafted and signed in Thailand. Its founding principles were negotiated and finalised in the Thai beach resort of Bang Saen, about 80 kilometres east of Bangkok and only 53 kms from the more popular resort of Pattaya (which didn’t exist at the time). The final document was eventually signed at Saranrom Palace, the HQ of the Thai Foreign Ministry, in Bangkok but the fact that it was incubated in Bang Saen would have been enough of a peg to hold a series of commemorative events to make the resort a must-visit spot on the ASEAN tourism circuit.

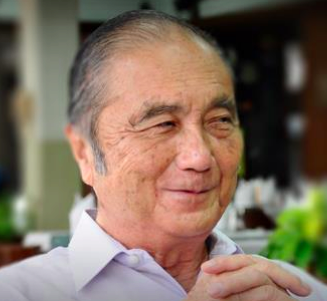

Prof Dr Sompong Sucharitkul |

The key player behind the formation of ASEAN was the late Thai Foreign Minister Dr Thanat Khoman, one of the country’s best-known diplomats. A detailed account of his extraordinary role was published by his former Chief of Cabinet, Prof Dr Sompong Sucharitkul in the Rangsit Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities (Volume 2, Number 1, January – June 2015).

Writing in his 2015 capacity as Emeritus Dean, Faculty of Law, Rangsit University, Prof Sompong recounts the rationale of Dr Thanat’s thinking. He notes:

Prof Sompong notes the prevailing geopolitical context of the 1960s, the internal upheavals and the nation building under way in Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand as they struggled to maintain their post-World War II freedom and independence. As many other international organisations were emerging at the time, Thailand had already taken advantage of one opportunity – to have the UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific located in Bangkok.

The account contains some fascinating insights about how Dr Thanat, accompanied by Prof Sompong, personally visited leaders of Indonesia, Singapore, the Philippines and Malaysia to sell and rally support for the ASEAN deal.

In Malaysia, he discovered that Malaysian Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman spoke fluent Thai because he had studied at Thepsirin college in Bangkok. Singaporean leader Mr. Lee Kuan Yew, wanted to know if Thailand was ever going to build the Kra Canal because of the threat it would pose to his own grand plan to develop Singapore as a trading port at the centre of the trading routes.

The Indonesians were apprehensive about the presence of foreign military bases in the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand. In the Philippines, Prof Sompong refers to the friendship he struck up with the then young assistant to the Vice President, a certain Benigno Aquino, and how that friendship facilitated broader negotiations between the two foreign ministers.

He writes:

Eventually, all the regional leaders came on board. The drafting committee went to work.

The insights also indicate how the ASEAN tourism industry continues to violate one of the core objectives of the creation of ASEAN by promoting the “Southeast Asia” brand image. Prof Sompong notes that the pursuit of economic, social, cultural and political assimilation and integration was intended to be “a ray of light to allow ASEAN’s collective identity to replace the national variation within the collective”.

The insights also indicate how the ASEAN tourism industry continues to violate one of the core objectives of the creation of ASEAN by promoting the “Southeast Asia” brand image. Prof Sompong notes that the pursuit of economic, social, cultural and political assimilation and integration was intended to be “a ray of light to allow ASEAN’s collective identity to replace the national variation within the collective”.

He ends with the hope of what Thailand can achieve when it “awakens from her slumber” and “realise what a colossal monument she had succeeded in creating through her planning, architecture and actual construction.”

These missed opportunities also underscore my long-standing and frequently cited view that foresight is meaningless without hindsight. Yet, today’s travel & tourism events and agendas are dominated by so-called futurists, strategic thinkers, “thought-leaders”, social-media gurus and techno-babblers who know everything about start-ups and asset value but nothing about the industry’s own heritage and historic value.

Prof Sompong would be the best keynote speaker to officiate at the ASEAN Tourism Forum in Chiang Mai in January 2018. Having missed this month’s opportunity to celebrate Thailand’s role in the formation of ASEAN, the tourism industry still has a chance to make up for it at the ATF 2018.

The full text of Prof Sompong’s article can be downloaded by clicking here: http://www.rsu.ac.th/rjsh/download/RJSHVol2No1-01-08.pdf

Further reading: http://asean.org/?static_post=asean-conception-and-evolution-by-thanat-khoman

Liked this article? Share it!