9 Aug, 2017

ASEAN@50: New book shows how ASEAN tourism undermined the ASEAN Miracle

Bangkok – When ASEAN marked the 50th anniversary of its founding on 08 Aug 2017, let the record show that the travel & tourism industry of Thailand, where ASEAN was born, negotiated and signed, did nothing, absolutely nothing, to commemorate the event. Neither did the Ministry of Tourism & Sports, nor the Tourism Authority of Thailand, nor the Tourism Council of Thailand, nor the PATA Thailand chapter nor any of the private sector associations organise a single event to mark the founding. They did nothing to publicise the VisitASEAN@50 campaign as well as Thailand’s hosting of the next ASEAN Tourism Forum in January 2018.

The only commemorative events organised were by the Thai Foreign Ministry, including an “ASEAN Special Lecture Series”, an ASEAN Day Reception and an exhibition on the 50th Anniversary of ASEAN with special display of replica of the ASEAN Declaration. According to the MFA, these activities “aim to promote Thailand’s leading role as a co-founder of ASEAN, emphasize ASEAN’s growing role in the Asia-Pacific region, and raise public awareness about ASEAN.”

Travel & tourism, arguably the most successful economic sector under the ASEAN umbrella, obviously saw no need to do any of the above. To understand why, get a copy of “The ASEAN Miracle”, a recently published book by two eminent Singaporeans, Prof Kishore Mahbubani, Dean of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore, and Jeffrey Sng, a former diplomat now living in Bangkok. Released earlier this year in time to commemorate the 50th anniversary, the book identifies the critical weakness of the 10-member grouping thus:

A phenomenal overview of what is arguably the world’s most diverse economic, geographic, social, cultural and political region, “The ASEAN Miracle” is a sweeping panoramic view of the colourful history that has shaped the 10 countries. In clear, simple language, and without a single chart, illustration or photograph, the book regals the reader with a page-turning account of the dynamics of change. Many personal anecdotes and insights from Prof Mahbubani’s participation in various meetings offer some eye-popping details on the horse-trading that occurs behind the scenes of international agreements.

According to the authors, “ASEAN has achieved a miraculous peace dividend. Its extraordinary achievements are deserving of the Nobel Peace Prize. But the prize is unlikely to be awarded any time soon. There is a widespread lack of knowledge about ASEAN and a baffling tendency to belittle its many accomplishments. It must also be said that ASEAN is not always its own best advocate.”

The book is of remarkable relevance to travel & tourism. The rich history of ASEAN so brilliantly outlined in the book is what travel & tourism sells for a living. Indeed, its entire package of strengths, weaknesses and threats and opportunities is a virtual template for ASEAN tourism to do its own internal SWOT analysis and assess its own past, present and future.

The book identifies the three most important weaknesses within ASEAN as being the absence of a natural custodian or leader, which is aggravated by the second weakness: the lack of strong institutions. These two in turn lead to the third weakness, viz., the lack of a sense of ownership among the peoples of ASEAN. All three feed on each other.

But these weaknesses were not always weaknesses. Twenty-five years ago, a group of visionary ASEAN travel & tourism industry leaders took the lead in harnessing all the strengths of ASEAN to launch a pivotal event known as Visit ASEAN Year 1992. Designed to mark the silver anniversary of ASEAN, VAY succeeded because the then six members of ASEAN got everything right. A major contributing factor was that the six ASEAN national tourism organisations operated independent of the ASEAN secretariat, and self-managed their own campaigns and projects.

All those strengths dissipated after the ASEAN bureaucracy took over. Tourism, one of ASEAN’s most promising economic, social, cultural forces, became a headless horseman and a victim of the system after the dissolution of the Kuala Lumpur-based ASEAN Tourism Information Centre in 1996 and its absorption into the ASEAN headquarters in Jakarta. The expansion of ASEAN to include the Mekong countries also saw the financial contribution system veer down to the lowest common denominator. Indeed, the expansion of ASEAN membership paradoxically became both a strength and a weakness. The final nail in the coffin came with the retirement or other changes in position of the ASEAN NTO chiefs whose personal camaraderie had been a major conduit of positive energy for the VAY.

The ASEAN tourism sector never recovered from those multiple whammies of losing focus, leadership, funding and institutional support. In spite of many other agreements and declarations on promoting ASEAN a single tourism destination, the ASEAN brand image suffered to a point where a USAID-funded consultancy recommended changing the marketing tag-line to “Southeast Asia.” So low did the ASEAN tourism brand image sink, that Visit ASEAN Year 1992 does not even rate a mention in the book.

Messrs Mahbubani and Sng make it quite clear what they would like to see happen next.

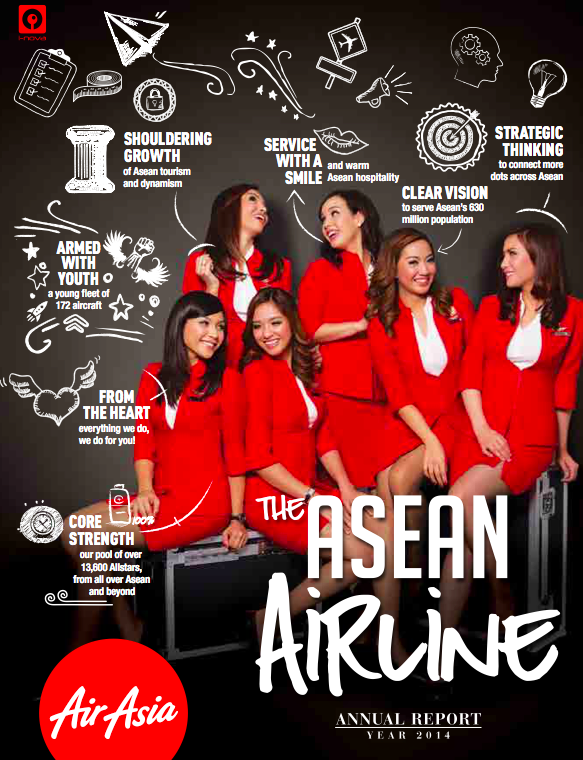

Travel & tourism can make a critical contribution to the success of this dream by enhancing the sense of public ownership of ASEAN. Indeed, tourism is a logical conduit and catalyst. The sense of ownership which faded after VAY 1992 was revived to some extent not by the ASEAN NTOs but by AirAsia. The airline’s CEO Tony Fernandes, an expat Malaysian of Indian origin, is a towering example of all the brand-building and entrepreneurial skills that the book identifies as ASEAN’s core strengths. By branding AirAsia as an ASEAN airline, he did more to enhance the ASEAN sense of ownership than a million man-hours of ASEAN tourism meetings.

Other important ASEAN weaknesses which go unmentioned in the book are an inability (or reluctance) to learn from the lessons and mistakes of history, a lack of transparency & accountability and appalling communications platforms. The ASEAN secretariat’s entire communications apparatus is dominated by meaningless press releases and communiqués which are full of bland, jargon-strewed sloganeering, exactly as they have been for the last five decades. Virtually none provide a plain-language explanation of how ASEAN’s work can benefit the common man.

ASEAN meetings also see delivery of enormous amounts of quality research and data on many subjects. The vast majority of it is well worth putting into the public domain, and could save the private sector, especially small and medium enterprises, millions of dollars worth of time and money in gathering it from other sources. Why this treasure trove of data is considered classified information remains a mystery.

“The ASEAN Miracle” proves that the miracle is still evolving and could be quickly undermined by bad decision-making. Visit ASEAN Year 1992 was the original ASEAN Miracle, a grand success story that became a grand failure. If just that regression is carefully dissected to learn from its mistakes, and the many valuable recommendations made in the book implemented to the letter, the dream of the ASEAN Miracle could still materialise in the next 50 years. As tourism is the world’s only industry of peace, it could perhaps play a major role in helping ASEAN win that elusive Nobel Peace Prize.

Liked this article? Share it!