3 Aug, 2013

Han Chinese Becoming Fluent in Uygur, Building Understanding, Culture

Xinjiang, 2013-08-02 (China Daily) It was after 10 pm in Urumqi, capital of the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region, and Zhu Xiaomei had just finished her Uygur language evening class, which she has been attending after work for almost a year.

|

|

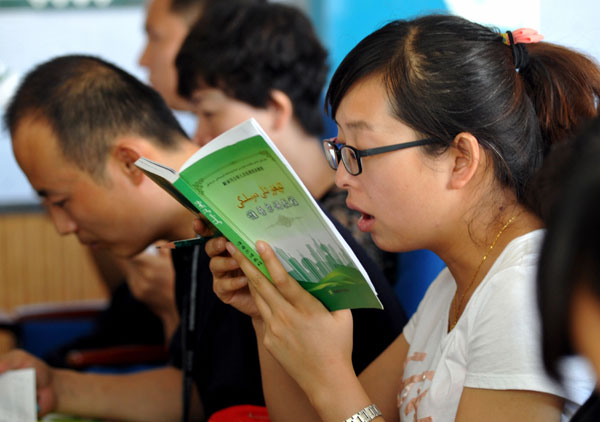

A student reads a Uygur book at Xinzhou training school in Urumqi. Photos by Yao Tong / for China Daily |

The strict pronunciation exercises had made her throat sore and the heat in the small classroom had left her tired and drained.

Zhu and 49 other students, most of them Han Chinese, had been studying in the room for two hours.

“I hope that one day I will be able to speak Uygur as fluently as my Uygur colleagues speak Mandarin.

“I’ve always believed that Han Chinese in Xinjiang need to learn some Uygur. After all, the Uygurs are encouraged to learn Mandarin, and bilingual education should work both ways,” said the 34-year-old legal consultant.

On her way home from work one day in August last year, Zhu noticed a billboard advertising “Crazy Uygur” courses at Xinzhou Training School, so-called because students are encouraged to shout out the phrases they’ve learned.

She signed up for the 1,500 yuan ($245) one-year course and has been attending the evening class three times a week ever since.

“It’s something I’ve always wanted to do. I’ve learned much more than just the language during the past year and now I understand more about the Uygur culture and traditions. The more you understand those things, the fewer misunderstandings there will be,” she said.

Xinzhou training school launched its Uygur training program in 2010 after Wang Jiansheng, the principal of the private institution, realized there was a demand for language classes. “Many people asked me where they could learn the Uygur language, so I decided to give it a go,” Wang said.

More than 900 students attended classes during the first year, and the figure has now risen to more than 2,000. “The students come from all sorts of background: businesspeople, doctors, government workers and teachers. The youngest student is just 6-years-old,” Wang added.

The star teacher

Behind the most popular course at the school, there’s a star teacher. Chen Yuhua, 51, has developed her own teaching methods, based on her experiences as a teacher during the 30 years since she graduated from Xinjiang University with a degree in Uygur studies.

|

|

Chen Yuhua, 51, gives an intensive, 20-day Uygur language course for community workers in Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region. Photos by Yao Tong / for China Daily |

Although the training school employs three teachers of Uygur, Chen is training a new teacher who will soon be qualified to join the team. That will allow the school to recruit more students. As it stands, Chen has to teach more than eight hours every day just to keep up with the demand for classes.

Two other private training institutions, Sanlian and Tianxiang, also provide Uygur lessons, but they are in the same boat as Xinzhou; a dearth of qualified teachers means both have long waiting lists.

“Many teachers allow students to write Chinese characters that are phonetically similar to the sounds of the Uygur words in their textbooks, so they will have a guide to pronunciation, but that’s something I strictly prohibit in my class,” said Chen, her voice husky after many hours of teaching.

She said some people are surprised to see a Han Chinese teaching Uygur, but she regards being Han as an advantage: “I know the words non-native speakers have difficulty pronouncing, and I know how to master them because I’ve been there myself. Plus, I think my Uygur is almost as good as native speakers after more than 30 years’ practice.”

No matter whether students sign up for a short, intensive training course or a full year, Chen always begins by teaching them the 32 letters of the Uygur alphabet and makes sure they can pronounce each one perfectly before moving on. To set a good example, she always pronounces the letters with great emphasis. It’s easy for visitors to identify Chen’s class among the maze of rooms in the school – all they have to do is to follow her loud voice. “Some people have even asked if the school will soon offer voice-training classes,” she laughed.

The culture carrier

Zhu said she’s been admonished by Chen so many times that’s she’s accustomed to it, “Although most of us are learning Uygur as a hobby, Chen is still very strict.”

When Chen noticed that some of the students in Zhu’s class weren’t giving 100 percent, she paused and asked them to speak louder to “wake their brains up”. “It’s disrespectful to speak to people using poor pronunciation,” she said.

Chen requires all her students to be able to sing a song and read a poem in Uygur. “There are many respectful expressions in the language, especially those used to address elderly people. Language is the carrier of culture. When people understand each other’s cultures, misunderstandings can be eliminated and that will, hopefully, resolve many of the conflicts in Xinjiang.”

Duo Yan, 56, has been studying Uygur for approximately a year. She has made such good progress that she attends Chen’s advanced class and is able to conduct relatively complicated conversations. One of the added benefits of learning the language is financial.

“I went to buy some dried dates from a street vendor a couple of days ago. When I asked the price in Uygur, he looked a little surprised but then smiled and said he’d give me a discount because I’d spoken to him in his own language,” said Duo, beaming with pride. She added that it wasn’t the first time that had happened.

“As someone born and raised in Xinjiang, I think it’s a pity I’m unable to speak Uygur properly. It’s not an easy language to learn, especially for older people like me, but I am surrounded by teachers, such as the street vendors,” she said.

Duo works for a company that sells elevators. Because she has to do household chores after her evening classes, she has developed the habit of arriving at work about 20 minutes early so she can review the points she’s learned the night before. She also takes her textbook to the offices of a nearby company that runs a Uygur website so she can practice with staff members during the lunch break.

When she offers tea to Uygur clients in their own language, they often ask if the company sent her to learn it. When they discover that she took the course of her own volition, they give her the thumbs up. “I think it’s helped the company seal a few deals,” Duo said.

Chen said Duo is a diligent student, but she needs to put more emotion into her spoken language, and that it should be a relatively straightforward task for a Han Chinese raised in Xinjiang, because the intonations of the Uygur language have long been integrated with the Xinjiang dialect.

Duo said she wishes her parents had taken her to learn the language when she was a child, like many of her classmates at the school. “I envy the speed at which they master pronunciation,” she said.

The alphabet song

Zhang Jinhua, loves to sing the “alphabet song”. The 7-year-old girl has already memorized all 32 letters, even though she only joined the class 15 days ago.

|

|

Seven-year-old Zhang Jinhua (left) is one of the youngest students attending the Uygur language class. Photos by Yao Tong / for China Daily |

“Her father can’t speak Uygur and sometimes he finds it difficult to do business in Kashgar. He insisted I take her to Uygur classes during the school holidays. She seems to be a fast learner,” said Zhang’s mother, 31-year-old Chen Yaning, who decided to join the class to keep her daughter company.

“My father let me talk to his Uygur friends on the phone, and said I will be his translator soon,” Zhang said.

“Don’t tell anyone that I have a secret teacher,” she whispered after singing the alphabetic song. Her secret teacher turned out to be Mehmut, who owns a naan bread shop which Zhang often visits to buy the flat, round bread for her family.

“One day I told the owner that I’d started taking classes. I spoke to him in Uygur and said I wanted three naans. He made a deal with me; he teaches me one sentence for every naan I buy,” said Zhang. After counting the number of naan she has bought since then, she proudly announced that she has learned nine sentences so far. “The first thing he taught me was, ‘This naan is delicious!'” she smiled and translated the phrase into Uygur: “Nan bek yeyixlik!”

Employment advantages

Li Hongling hopes that learning Uygur will eventually make it easier for her 11-year-old daughter to find work. “Speaking Uygur will always be an advantage in Xinjiang’s employment market and now people are required to pass a test in Uygur before they can take up a job with the government,” said Li, 35.

According to a directive issued by the regional government in April 2010, all newly recruited government workers must take Uygur language courses and pass exams before reporting to their posts. Workers already employed by the government will also receive lessons. They will not be promoted or become heads of townships or villages if they fail the tests.

At the moment, Chen spends her mornings teaching 40 community workers from the Gangcheng district of Urumqi, where 30 percent of the residents are Uygur. For most of the students, the 20-day intensive course is their first experience of the language.

“No one can learn a language in such a short time, so all I can do is teach them a learning technique,” said Chen, who told her students at their first class that if they really want to better serve the Uygur residents, they must continue to study when the course comes to an end. She urged them to talk to the locals because they are the best teachers.

Chen taught the group to say “As-salamu alaykum“, an Arabic greeting that means “Peace be upon you”, as a respectful greeting. However, some people complained and said it would be inappropriate to use the phrase because only Muslims should use it, citing the fact that Islam is the dominant religion among the Uygurs.

“I told them that it’s just a normal expression in the Uygur language and equivalent to saying ‘ni hao’ (‘Hello’) in Mandarin. I don’t understand why they like to make simple things so complicated.”

Cui Xuhua, 43, deputy director of the Gangcheng administrative committee, studied Uygur briefly last year, but admitted he’s forgotten most of what he learned at the two weeklong courses he attended.

“The teacher told us to remember the pronunciation, rather than teaching us to recognize the letters. As a community worker, I feel it’s important to have a direct conversation with residents, and not use an interpreter. Otherwise, it feels as though there’s a barrier between us. That could prevent us from understanding what the residents really want, the things they like and those they don’t. Understanding people makes all the difference.”

Contact the writer at cuijia@chinadaily.com.cn

Liked this article? Share it!